Anthony Joshua reveals why the person who challenges him every day continues to be his hardest opponent: himself

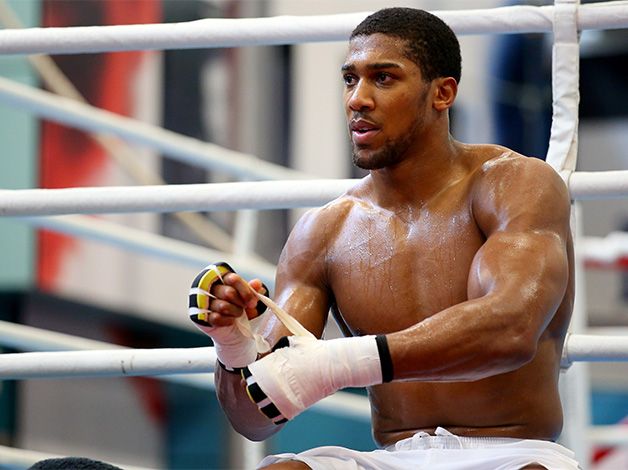

The world heavyweight champion is working out next to a middle-aged woman who is mostly ineffective with pink kettlebells at 7 p.m. on a Monday in the fall. Anthony Joshua appears almost hilariously out of place in this London gym club’s everyday routine. However, at 198 cm tall and a slender 108 kg, the 27-year-old is remarkably dissimilar in most environments. And that involves competing against unfortunate opponents in the ring.

Joshua is only getting warmed up right now. In order to strengthen his neck and core, he first foam rolls, then planks and bridges, the last one with his head resting on a Swiss ball. Next he goes to the pneumatic Keiser cable machine, an exotic piece of equipment that allows for low-impact, high-speed training by using air pressure as resistance instead of iron plates. To strengthen his shoulders, Joshua begins with gradual rear delt flies and external rotations.

“I’m guessing you was expecting some spit and sawdust gym?” he grins, reading MH’s mind. Well, yes. You know, chalk-coated barbells and Phenomenal by Eminem on repeat, just like in Southpaw . . . Joshua guffaws, as Mr Vain by Culture Beat pumps out of the speakers for the second time this session. “Don’t worry, it’s gonna get fun in a minute.”

Big Influencer

Power – the kind required to knock out 19 heavyweights in 19 fights since Joshua turned pro after winning Olympic gold in 2012 – does not come from heft alone. In both physics and physiques, power is strength multiplied by speed. As Joshua executes a variety of explosive punching movements and woodchoppers, his strength and conditioning coach, Jamie Reynolds, constantly demands more speed. Mid-set, Joshua strenuously ignores the gym-goer lingering nearby, smartphone in hand. But as the gym-goer turns toward the exit, Joshua stops and calls after him: “I didn’t realise you were leaving.”

Though they might pretend not to be, everyone in the room is watching. A couple of skinny young guys on the lat pulldown machine look on forlornly as he works through TRX body saws, pikes and inverted rows. A barrel-chested, keg-bellied powerlifter, waddling proudly to the water fountain, sneaks a sideways glance at the heavyweight champion, crab-walking with minibands around his knees and ankles to activate his glutes. He pounces through speed skater squats like a big cat.

Meanwhile, Joshua is watching Joshua. As the other inhabitants of the weights room continue with their curling, rowing and pressing, Joshua performs increasingly heavy trap bar deadlifts. By the time he sits on the Wattbike, which measures power output, he’s been working out for the best part of two hours. That’s not counting this morning’s training session, of course, for which he left the house at 8am before returning at 2pm.

Reynolds pulls out a notebook as Joshua plugs in his headphones and starts pedalling. Grunting, he goes deep into the pain cave and shatters his times from the previous session. He gasps for air to neutralise the lactic acid burning in his quadriceps; nearby, gym-goers plod on treadmills, barely breaking sweat. The session is over.

Core Values

It’s now past 9pm and Joshua needs to eat. Showered and changed, he gives MH a ride back to his place. If you were expecting the kind of mansion occupied by Southpaw’s Billy Hope, you might be surprised to learn that Joshua lives in a modest ex-council flat with his mother and niece. “I can’t get too comfortable,” he explains, sitting shirtless on a massage table parked in his front room. “All I need is a place to rest my head . . . At the minute, I’m managing pretty well. Everyone’s happy.”

Joshua certainly seemed happy during tonight’s session, as opposed to looking like … “Like I’m gonna 𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁 someone?” he finishes. “No. You think about the fight. But the battle’s more within myself, to get better than where I was in my last camp, my last session. And in between sets or intervals, I like to have a laugh and a joke. It builds a confidence that I am fit, that I can go through the pain and have fun while I’m doing it.”

Indeed, there are some who accuse Joshua of spending too much time in the gym, deriding him – presumably when safely out of fist’s reach – for being more bodybuilder than boxer. Fellow UK heavyweight Tyson Fury once remarked that Joshua resembled “a pumped-up weightlifter out of his mind on drugs”. (“I don’t know what else I should be doing,” counters Joshua.)

In fact, Joshua’s genetic gifts are a double-edged sword: his height and frame give him reach, but those long levers make it harder to generate power. Even so, he throws a punch that, to steal a phrase from veteran boxing writer Kevin Mitchell, “would have decapitated a bull”. That’s testament to Joshua’s gym work, particularly on his core, which transfers power from lower body to upper. “Cut your arms and legs off and you’re left with a trunk, which you need to be as strong as possible,” he says. “That’s why we work everything from the calves to the neck.”

Plan of Attack

Of course, boxing is not solely a contest of physical condition – otherwise Joshua would already be undisputed champion. “From the neck up is where you win or lose the battle,” he says. “It’s the art of war. You have to lock yourself in and strategise your mindset. That’s why boxers go to training camps: to shut down the noise and really zone in. If I can control my mind, then I’ll be unstoppable.” While crowds might urge him to charge in like Tyson (Mike, not Fury), Joshua is more circumspect, trying to make the minimum of mistakes while looking out for those of his opponent that he can punish. “There are two types of warriors: the one that rides through on his horse and tries to slay everyone, and the sniper. I try to be more like the sniper. Bang. Bang. Bang. Break them down, shot by shot.” In his downtime, Joshua plays chess – as well as first-person shooter video games.

Discipline is a boxing watchword. It’s fair, if as clichéd as a Rocky plotline, to say that the sport gave Joshua exactly that. As did the electronic tag he wore for 14 months as a teenager having been put on remand for “fighting and other crazy stuff” and facing a potential 10-year prison sentence. “Imagine being at home every day at 8pm for 14 months: Christmas, New Year, birthdays,” he says. “That routine was a really good start to my boxing career. I took a positive from it.”

He used the spare time to read about champions like Joe Louis. “He’s a good example,” says Joshua. “Louis was a beast in the ring but very respectful outside the ring. They were the days of class.”

Class – as in standards, respect, demeanour – is a repeated refrain in any conversation with Joshua. For instance, when asked if he is a violent person, he is quick to shoot such notions down. “No. I was raised well. My parents are from Nigeria; their culture is respectful. Very respectful. But I learnt that you have to be determined. It’s not violence or aggression. It’s sheer determination.”

But what about that almost malevolent grin that hits his face when he’s systematically breaking down his opponents? “It’s weird because obviously I’m nervous . . . I don’t know where that comes from.”

Does he take pleasure from punching people? “Yeah, I enjoy the job. As you saw in the gym, I have fun.”

Joshua refers to fights as “projects” (“I have a timeframe, a deadline to work towards”) and he’s unperturbed by opponents – even one as storied as the 41-year-old great Wladimir Klitschko, who he defeated in an 11-round epic on April 29. “You show respect for what he’s achieved, but you have to rise to the occasion,” he says. “You try your best and walk out the king. I definitely get a bit nervous,” he admits. “But then I think: you know what the greats do? They make the hard and impossible look easy.”

It’s now 11.30pm. Joshua has barely put down his fork before his PR hands him a stack of boxing gloves and T-shirts to autograph. Under the name “Anthony Joshua”, and his own gold-penned signature, the screenprinted legend on the T-shirts reads: “Stay hungry.”